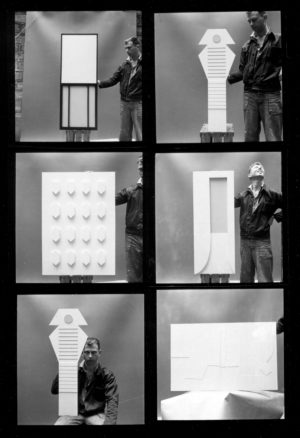

In Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris, two stretched canvases—the upper one painted white, the lower one gray—are mounted within a continuous framing wood strip painted black. The white panel is flush with the narrow framing edge; the gray one is recessed behind a frame that is (on its outer edge) continuous with the upper one, but expanded on its inner edge to twice the width. The gray canvas is also vertically traversed by two narrow black wood strips (derived from the window’s mullions) which cast shadows on its recessed surface. (Rudenstine 1988, p. 719)

In October of 1949 at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris I noticed the large windows between the paintings interested me more than the art exhibited. I made a drawing of the window and later in my studio I made what I considered my first object, Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris. From then on, painting as I had known it was finished for me. The new works were to be paintings/objects, unsigned, anonymous. Everywhere I looked, everything I saw became something to be made, and it had to be made exactly as it was, with nothing added. It was a new freedom: there was no longer the need to compose. The subject was there already made, and I could take from everything; it all belonged to me: a glass roof of a factory with its broken and patched panes, lines of a roadmap, the shape of a scarf on a woman’s head, a fragment of Le Corbusier’s Swiss Pavilion, a corner of a Braque painting, paper fragments in the street. It was all the same, anything goes. (Ellsworth Kelly in Coplans 1971, pp. 28–30)